Radio Erena: 10 December 2021

By Fathi Osman

It is an open secret that Alkaizan are preparing for a forceful return to power in Khartoum. “Kicked by the door, they will return by the window.” Says the bemused Ahmed Kassuri, a member of the Popular Resistance Committees of the restive Khartoum Bahri (North.)

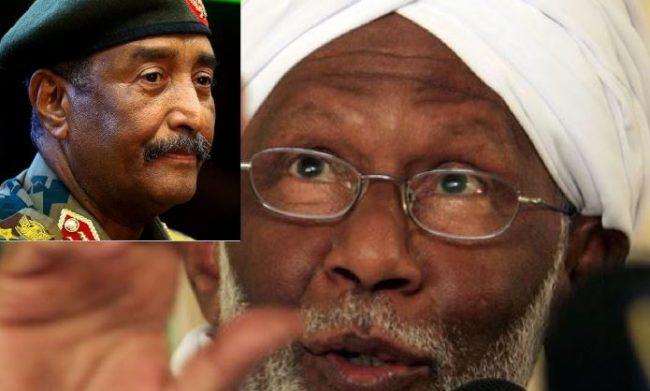

Alkaizan, (the singular Koaz) is the local misnomer of the members of Muslim Brotherhood Group. Its coinage is attributed to the eloquent Dr. Hassan Turabi, the group’s leader and ideologue. Metaphorically referring to Islam as a river of bliss, he called his followers “Alkaizan”, (the Mugs) with which water is to be scooped for the parched. Currently, it is rather used for belittling and scorn. Scorn or not, Al-Kaizan, who lost power with the downfall of General Omar Bashir, are making their return to prominence through the latest coup of General Abdul Fattah Burhan.

As the de facto head of state, who built his carrier and reputation as a faithful lieutenant of the former dictator, Burhan had abruptly cancelled the power-sharing deal with the civilians reached in 2018 to usher Sudan throughout the transitional period.

On Oct. 25, he launched his desperate coup, arresting the Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and several of his cabinet ministers, mainly the representatives of Forces of Freedom and Change parties, the largest coalition of political parties and civil society organizations in Sudan’s history. He immediately dissolved the government, suspended certain clauses of the Constitutional Declaration, and finally, dealt a blow to the process of breaking up the old regime powerbase through disbanding the “Committee of Disempowerment” of Bashir’s regime, then arresting its key members.

At the beginning, Burhan tried tirelessly to convince his people that his stunt was not a coup, it was, from his point of view, a “correction of the trajectory of the Revolution.” All his attempts were in vain. Instantaneously, thousands of angry Sudanese rallied in anti-coup mass protests. Excessive violence was the security’s only way to deal with the protesters. So far, 44 protesters were killed, and several hundreds were injured. The earlier coups in 1958, 1969, and in 1989 taught the Sudanese that a coup is a fatal stab to their freedom. Burhan’s coup was not an exceptional case.

The festering relations and the subsequent quarrels among the generals and the politicians were the given excuses behind the coup, but the real causes are buried much deeper.

The Stereotyped Antagonism

Ever since the first coup of General Ibrahim Abboud in Nov. 17, 1958, just two years after the independence of Sudan from the British rule, the relations between the Sudanese Armed Forces’ generals and the politicians have been marked by mutual mistrust and contempt. The generals, trained to worship discipline and order by profession, see their counterpart politicians as undisciplined, self-gain seekers and ultimately a potential threat to the country’s stability and security, which falls under their sacrosanct domain. Burhan, in a recent frenzied speech days before his coup, described the armed forces as the ‘custodian’ of the Sudanese people. Some activists ridiculed the statement saying: “Why not then the generals babysit the Nation.” Such an attitude seems to be universal among people of uniform who oversee security. Describing the origins of the former KGB officer Vladimir V. Putin’s view of civilians, David Remnic, the author of the Pulitzer Prize winning book: Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire, says: “… the ascetic former officers of the KGB who were, thanks to their preparations and years abroad, comfortable in any setting yet who betrayed a steely disdain for all the ignorance and opulence around them.” Remnic shrewdly quoted Putin’s snap answer to Karie Couric in an interview: “I am not sure you understand what you are talking about.”

Sudanese politicians take the arrogance of the generals toward them easy, often with acerbic humor. By contrast, the generals react to the slightest reproach as a crime punishable by law under the article of “contempt of the armed forces.”

In a stark disparity to the generals’ idealistic self-image, the politicians, divided along a wide array of political parties, see the generals as narrow-minded fellows, politically incompetent, and deprived of the know-how essential to run the state. Therefore, the best places fitting them are the barracks, a theme repeatedly hollered in mass demonstrations today: “Soldiers: back to barracks.”

Since the establishment of the generals-politicians power-sharing deal to lead the transitional period in summer, 2018, misunderstanding and evil intents have been bogging down the march forward.

Dismantling the Ancient Regime: The Backyard Battlefield

At the core of the generals-politicians’ bickering lurks the dreadful task of breaking up the old regime’s resources, ideology, and power channels. During his thirty years in power, Bashir’s political façade, the Muslim Brotherhood, dominated all walks of life from economy to village administration. Ironically, it was the first time for one political party to exercise complete control over the state in Sudan. Hence, in 1999, the National Congress Party, led by Bashir, emerged as the leading party after the famous split in the Brotherhood between the General and the Sheikh: Al-Bashir and Turabi. A priority mandate under the Committee of the Disempowerment of the old regime is the dismantlement of the powerbase built in the past thirty years, including reforming the armed forces, the security, and the civil service.

To the dismay of the influential generals, such a process will place the conglomeration of corporations run by the armed forces under a civilian administration. Moreover, if the process continues it will indisputably neutralize, if not entirely dismantle the empire built by the Duglo Brothers: Hamdan (Hemeti) and his brother Abdul Rahim, the founders and leaders of the notorious Rapid Support Forces.

Depending on four-wheel drive light trucks with mounted calibers, The R.S.F arrived at Khartoum on orders from Bashir to quash the popular demonstrations. Hemeti, a one-time camel herder and trader, discovered that his patron’s regime was struggling against death throes. He swiftly shifted sides, announcing that his forces will not be used against the people.

Soon afterwards, the army and security used the R.S.F. to massacre hundreds of young men and women in front of the Armed Forces Head Quarter. On June, 3, 2019, hundreds of soldiers stormed the Sit-in venue where hundreds of the F.F.C supporters sat in a lengthy protest. In a shooting spree, the soldiers killed hundreds of protesters, raped women and burned some of the victims alive in their tents. To conceal the corpses of the victims, the soldiers used stones as weight-bearings, tightly tied the stones to their bodies and dropped them in muddy brownish waters of the nearby river.

As the objective of the heinous crime was to erode the support powerbase of the Forces of Freedom and Change, the bargaining lot of the F.F.C was gravely weakened. Reasonably, some of the F.F.C member parties refused any arrangement of power sharing with the military.

Although the wanton killings were new to Khartoum residents, the Rapid Support Forces, known in western Sudan as the Janjaweed (the jinni on a horse), committed atrocities on daily basis since its formulation as an armed forces support troops in 2013. The result was a long list of charges of crimes against the humanity vis-à-vis its file and rank. The R.S.F is also engaged in illicit economy of gold export. Economic columnist Alhadi Habbani estimates its gold export business revenues at 16 billion dollars.

The Mortal Mishmash of Corruption and Violence

The Oct. 25, coup was launched to abort the approaching transfer of power to the civilians in the Sovereignty Council on Nov. 17. Realizing that the civilians will accelerate the accountability procedures and will advance the demands for the armed forces and security apparatus reformation, Burhan pre-emptively and hurriedly launched his coup. “The very fact that Burhan felt compelled to launch a coup attests to the progress the transitional government was making in curtailing the power of the military and security forces.” Wrote Rebecca Hamilton to the Washington Post. Undeniably, Burhan’s mission is to apply brakes to the increasing anti-corruption and malfeasance processes.

Additionally, the hopeless attempts to legitimize the coup at a gunpoint added more fuel to the fire as the calls for independent investigations on the killing the protesters increased.

“The remnants of the N.C.P, and the R.S.F leaders, plus the army cartels are the main sponsors of the coup. They have amassed huge economic and political interests that they will fight to protect, they are dead serious about that,” Declares Bakry Almedni, Professor of Public Policy at Long Island University, Brooklyn. He believes that the strong support behind the coup will logically come from the old regime’s members and supporters. Corruption and violence are comfortably scratching each other’s backs; the guns and the banknotes are now working in cool harmony.

Disempowerment threatens the lifeline interests of the generals and the old regime backers. Giving up power and wealth is not an option for the generals at the top today.

Amid this intense fray, one wonders: where is the Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok?

The Unenviable Condition of Hamdok

Abdallah Hamdok, the former U.N. senior functionary rose to power on outstanding approval ratings after rejecting the portfolio of the Ministry of Finance during the last days of the old regime. The Freedom and Change Coalition have chosen him and called the streets to back him with unwavering support.

A month after the coup, Hamdok was brought to the hall in front of world TV cameras to sign an agreement with the victorious general Burhan. There was a growing international pressure to bring Hamdok back to his post, but not his ‘constituency’: the F.F.C.

In his interview with Al-Jazeera, he confirmed his earlier consultations with all the political parties, saying that he wasn’t under whatsoever pressure to sign the agreement.

Professor Almedni believes that Hamdok was only representing himself in his agreement with the generals. The reasons behind his signing the unpopular deal are so far speculative, but a closer look at his political trajectory will shed some light into his political conduct past and present.

Abdalla Hamdok assumed his job knowing that he is in a precarious position of serving more than a master at the same time. His impossible job was further complicated with division, post-jockeying among the F.F.C., and the increasing pressure from the generals’ side. Rather than to be loyal to his political backers, he chose the awkward job of mending the fences between the politicians and the generals. A job which can simply be described as impossible as the generals didn’t hide their intentions of launching their coup sooner or later. That wasn’t a secret, as the generals had publicly threatened to take over and had already staged a mock-coup soon before Oct. 25.

Trained and inspired by U.N. timid diplomacy, Hamdok tried, ineffectively, to play the heroic role of the mediator. As a result, he distanced himself from his political stronghold weakening himself as well as his cabinet. When he accepted his reposting, he still maintained the dreamlike hope that he might one day succeed in handling the situation arising after the coup: to save the transitional period and to prepare the country for the elections in 18 months, despite his knowledge that the generals were throwing roadblocks in his path. He also knows well that breakneck elections will only mean the endorsement of the disguised return of Alkaizan.

The Comeback of Alkaizan

The mainstream Islamist Political Movement is composed of the dormant Sophist Tariqas, the pro-Bashir N.C.P, and finally the Popular Congress Party. This opposition party was established to rival Bashir’s Congress Party by Turabi.

December 2018 Revolution sent the N.C.P to the background, but the party still holds a firm grip on economy and security. In addition, it enjoys steadfast support inside the armed forces. Many eye-witnesses confirmed the party’s militia role in the massacre of June, 30.

Many believe that the coup of Burhan was planned by Alkaizan for a fresh return to power. The N.C.P has not officially announced its support of Burhan’s coup, but its members are rubbing their hands in glee in the secret.

In contrast, the Popular Congress has condemned the coup and asked the generals to return to their barracks.

“We have a bitter experience with the military. General Bashir had once stabbed us in the back; we will never repeat that mistake of trusting the generals.” As Kamal Omer, the Secretary General of the P.C.P has told Amir Babikr, the Sudanese novelist and political commentator.

With the division among the Islamists and the stubborn opposition of the left, Hamdok has a shallow pool to draw his government members from. The only choice left for him is to bring back the unknown second-row N.C.P members.

Faced with an increasing lack of support, Hamdok appointed undersecretaries to run the day-to-day routine of the ministries. Most of those chosen were either N.C.P members or close allies to it during its rule.

Journalist and activist Durra Gumbo tracked back the C.Vs of some of the newly appointed undersecretaries; she found out that some of them were staunch supporters of Bashir who had an antagonistic stance against the Revolutions. Moreover, Burhan enjoys decisive executive powers: he appoints the ministers of defense, interior and information, without a nod from the prime minister. He brazenly appointed General Ahmed Almufaddal, a former regional governor under Bashir as head of the General Intelligence.

Finally, several factors will decide the sweeping return of Alkaizan to the scene. Burhan’s coup opened the door for their return. The impotency of Hamdok and the blind support from certain quarters in West and some predatory regional planners will have additional damaging impact. The streets will resist the military rule, besides, the political unrest will, undesirably, prevail.